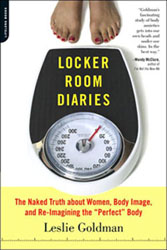

Locker Room Diaries

Permanent link All Posts

Author Leslie Goldman

In a Chicago gym locker room, a little girl, maybe three years old, climbs aboard a giant scale.

To her, the newly discovered apparatus is a toy with no other purpose than fun. She jumps up and down gleefully and calls for her mother to come witness her game. Her mother exclaims, “That’s great, honey,” and lifts her daughter off the scale and steps onto it herself. Immediately, the mother’s demeanor changes, she frowns, and drops her head down. Then, she gets off the scale and her daughter climbs back on it, this time imitating her mother’s actions, dour face and all.

This scene and others like it were observed by Leslie Goldman, an avid exerciser who has logged many hours in her gym, in her gym’s locker room and even on that scale. “I would hear women making horrible comments about their bodies in the locker room, complaining to each other, looking in the mirror, and squeezing their thighs and butts,” she says. “I would see them get on that giant scale and you could just tell that number was ruining their day.”

Goldman—who has always been interested in body image issues and who, years ago, struggled with her own eating disorder—would jot down her locker room observations into a diary. Eventually, her research grew and she would come to spend five years interviewing hundreds of women in gym locker rooms about their bodies and body image, compiled in

Locker Room Diaries

.

The author will speak at the Chicago Brain Power for Girl Power Think Tank, sponsored by Jewish Women International, at the Spertus Institute in Chicago on Wednesday, Oct. 29, a new program that brings together 50 Jewish women to learn about and debate issues that affect Jewish girls.

A Buffalo Grove native who now resides in Roscoe Village, Goldman discovered that many women are unsatisfied with their bodies. Her findings are no surprise to any woman who has been to a gym or to any man who as been asked the dreaded question: Does this make me look fat? Just look at any magazine or website and you’ll see ads for diet and weight loss products.

“It seemed like everyone has something that they wish was bigger or smaller or tighter or taller,” she says, “and it’s very rare to find the woman that is so happy and accepting of her body as is, and that doesn’t bode well.”

It doesn’t bode well at all. In fact, poor self-body image often develops into eating disorders—the third-most frequent chronic illness among teenage girls according to Goldman—which, she says, occur because of a mix of genetic and environmental factors. There are approximately 8 million cases of diagnosed eating disorders in the nation, with the highest fatality rate of any psychiatric illness, according to the author. And the statistics only represent the diagnosed cases. Many more people suffer from “disordered eating,” where they will skip occasional meals or pop a laxative every now and then if they’re feeling fat.

Jews, particularly Jewish women and girls, are certainly not immune to body image issues and eating disorders. Goldman is one such Jewish woman who developed an eating disorder—anorexia—during a time of transition, her freshman year of college. She was a straight-A perfectionist who had just gone off to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she was majoring in nutritional sciences, a common major for someone with eating issues, according to the author.

“I developed an eating disorder as a way to assert control over a seemingly out-of-control situation,” she says. “I was at a phenomenal school and felt a little unsure of myself and lost. Counting calories and monitoring what you eat is a great diversionary tactic so you don’t have to think about the deeper problems on your mind.”

Goldman dropped 30 pounds her first semester of college. When she returned home for Thanksgiving, her parents were frightened by her drastic weight loss and took her to a therapist.

During another break from school, she recalls visiting her grandmother’s house and refusing her grandma’s homemade matzoh ball soup, which she had always loved in the past, after discovering the soup’s fat content. Her grandma was crushed. “In Jewish life, there’s a lot of joy to be had in sitting around the table with your family and celebrating and reminiscing over food,” says Goldman, “but it can be very oppressive at times for [people with body image issues].”

Goldman struggled with anorexia throughout college and suffered a couple of relapses, including her senior year of school, during another big time of transition, when she was living in a house off-campus with seven women, six of whom had an eating disorder, and five of whom were Jewish. Finally, after college, she took her recovery more seriously and conquered her illness.

Goldman refers to her story as a “cliché, textbook” case of the type of Jewish girl who developed an eating disorder. Like her, young women with eating disorders often are often driven, straight-A students wanting to help everyone else before they help themselves.

Goldman believes that many environmental factors make Jewish women and girls susceptible to eating disorders, as was the case for her.

She sees that some Jews come from middle to upper socioeconomic strata, affording them more access to gyms, low-fat pricier foods, fashion magazines with skinny models, and vacations where one wears a bathing suit in front of others.

Plus, at the same time, many Jewish families have high expectations of their children, according to Goldman. “Many Jewish families put a lot of emphasis on education and striving to achieve and giving back and being the best person you can possibly be, which are all wonderful things,” says Goldman. “But these concepts are also a lot for a person to handle, especially a young girl trying to figure out who she is.”

Finally, at times, there aren’t always firm boundaries in Jewish families between children and their parents, says the author. “That doesn’t leave a young woman going off to college in a very good position in terms of who she is on her own when she is away from her family,” she says.

Today, in addition to being an author who tours college campuses and other venues with her book, a healthy Goldman writes for women’s magazines like Health and Women’s Health and blogs about body image, nutrition, fitness, and feminism for iVillage at The Weighting Game.

Despite triumphing over her illness and even lecturing on the topic, she still sometimes battles the less-assured version of herself. “I have good days and bad, and now the good days far outnumber the bad days. But even though I’m a body image writer, I still [sometimes] ask my husband, ‘Does my butt look big in these pants?’”

Goldman fights her impulses to make comments like that because as she and her husband think about starting a family one day, she is striving to pass down a healthy body perception to her children. She worries when she hears reports from her mother, a preschool teacher at a Jewish suburban Chicago school, of three-year-old girls rejecting their juice and challah because they claim they’re on diets.

The author says Jewish parents can take these steps to help promote a healthy self-body image to their children. First, parents need to make smart choices about the types of media, namely television and magazines, they allow into their homes. Some magazines feature “gaunt, emaciated models,” while others display healthier women with more meat on their bones—but all magazines, she adds, digitally manipulate and airbrush their models.

Also, parents should watch their words and actions around their children. Mothers, she says, ought to be careful about looking at their reflections in the mirror and making a disgusted face or going to the grocery store and picking up food only to declare it “too fattening” and putting it back.

Goldman hopes parents will transmit positive messages to their children, less about superficial beauty and more about what’s on the inside. “Send a really strong message about loving yourself for more than your body and praise our little girls for more than being pretty and cute,” says Goldman. “Don’t save the references about being strong for just the boys. Tell the girls they’re strong and smart and compliment them when they open the door for someone.”

As for that giant scale in her gym locker room? Goldman says she rarely steps onto it anymore. In fact, she rarely weighs herself at all, only about once a year. And not being tied to that number on the scale is a weight off her back. “I feel happy walking down the street not knowing that number,” a feeling of contentment she hopes to one day pass along to her children.

.jpg)