Becoming a Jew after the Holocaust

Permanent link All Posts

For centuries, Rabbis have used Naomi’s three attempts to send Ruth back home as an example of how to deter a potential convert, and with such dissuasion comes vague warnings of the persecution that is part and parcel of being a Jew. Perhaps no other event has stripped away obscurity and presented anti-Semitism in such stark black and white terms as the Holocaust. It hangs over Jewish history like a dark cloud, necessitating a distinction of life before and after. To become a Jew post-WWII is to know in grave detail just what the worst case scenario is. That said, the unofficial slogan of remembrance is “Never Again,” and while it may or may not hold true, the phrase points to something that has already occurred.

I arrived in this world and emerged from the mikvah with my family intact and unaffected by any ghosts of the past. My choice to convert has met with a plethora of questions and light opposition, sure, but my observance does not stir up pain for my relatives. Judaism does not for them beg the question of the existence of a God who allows such a thing to happen. Is it my own guilt or paranoia that makes me tiptoe around the topic, then, and feel that my grief for the 6 million should be carefully measured? After all, I think, I know them only as that collective number, not as individual names.

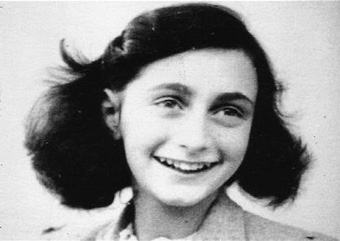

So sheltered from the Holocaust was I, in fact, that I hadn’t even heard of it until I read The Diary of Anne Frank at age 11. Out of sheer ignorance, I was less concerned with the events that had landed her in the Secret Annex and more empathetic to her misfit status within her own family; I, too, felt like the less favored daughter. Imagine my surprise when the epilogue landed on me like a pile of bricks, announcing Anne’s death as the inevitable ending that it was, but that I in my innocence never saw coming.

A period followed in which I can only be described as consumed. This was tricky for my parents, who were incredibly restrictive with music and television but never with books. Still, I had never dived headfirst into such a subject before and more than once the question arose as to whether I was old enough to handle it. This goyish protectiveness alone sets me apart from my generation of born Jews, who did not have the luxury of being sheltered from events that directly affected their own grandparents. Certainly Anne in her young age was not spared it. But unlike my campaign for access to MTV, I prevailed in my desire to understand how the Holocaust had happened, and my studies continued. Over time, I did ease up in my pursuit a bit, though I never resisted if the topic found me. Understanding continued to elude me, and it is this, at least, that I share with all Jews.

But before we get too cozy in our mutual outlook, a full confession must be given. My dark hair and eyes often lead others to presume I am Jewish by birth, and the revelation that I am not leads to inquiring about my heritage. (Scottish, Irish, French, Dutch, and German.) German? And when, ahem, did that side come to the U.S.? (1923 and 1925.) Their expression relaxes into an unmistakable look of relief. At least, they are thinking, I am not a descendent of them.

They are only partially correct. It is true that my great-grandfather came over first, and my great-grandmother followed two years later. From the safety of America, they watched their country go mad. His dislike of Roosevelt was only surpassed by his detestation of Hitler. She was nearly arrested by the Gestapo on a pre-war visit to her homeland. Tanks rolled through the streets, but still her family believed the Fuhrer’s assurance that there would be no war. “Look around you,” she said, incredulous, “Everyone in the world knows what is coming.” We’ll never know who, but one of her relatives promptly turned her in. It was only by luck of the train schedule that she was already in France by the time there was a knock at the door. Perhaps it was the uncle who would later write my grandmother, advising her to disregard the Old Testament in her Confirmation studies. Or was it one of the parents of the little cousins enrolled in Hitler’s Youth, whose photos in swastika-ed uniform were proudly sent to the States? There is poetic justice in my becoming a Jew, but it does not outweigh the guilt I feel by association.

I returned to my preteen preoccupation with the Holocaust during my conversion process, inflicting every movie and book on myself like emotional lashings I felt I deserved to earn my Jewishness. Funnily enough, my determination to get to the bottom of it two decades ago never led me to learn about Judaism, and even now, the two seem irreconcilable. I am expected to mourn the destruction of both Temples with abstinence from both food and armchairs, events from a time when my ancestors were likely polytheistic pagans, but grieving over losses suffered in the century in which I was born leaves me feeling like a poseur.

It was a conversation with a non-Jew that first forced me to defend my feelings. There it was, the question I was unprepared for: Why did I care so deeply about the Holocaust? Anne Frank once again acted as my ambassador when I recently revisited her diary. I had been fully expecting a nostalgic read but was instead struck by her talent and wry insight, with a writing style that should have decorated a lifetime of books. I don’t mourn Anne as the poster child of young lives snuffed out by the Holocaust; I grieve her as the author who never was.

The Rabbis of the Talmud noticed an odd thing in the story of Cain and Abel: When God corners Cain into a confession by telling him He can hear Abel’s blood crying out to Him from the earth, the Hebrew is actually ‘bloods,’ plural. From this, the Sages deduced that Abel’s murder was not just one life extinguished, but an entire bloodline. My family did not perish in the camps. Still, I do feel the loss of the individuals, the Jews my age who should be here but are not.

Kate Sample is a writer and Jew-by-choice living in Chicago.

.jpg)